E-Travel Log # 8: Schools in the Kalahari Desert

Dear students,

Matisa? (Pronounced mah-tee-sah.) That means ‘How are you?’ in the Nama-Damara (nah-mah dah-mah-rah) language. The response is '!gaia' (Click plus guy-yah). All this week, Lilia and I visited two schools in the Kalahari Desert of southeastern Namibia. While there, we learned a little Nama-Damara, so we’re going to start this report with a Nama-Damara click primer and, later, teach you how to count to ten in the famous click-language. We’ll also tell you about the Kalahari and our week there, challenge you with a guess-who animal poem and a Kalahari math puzzler and end with more of your questions, this time answered by Kalahari students. Enjoy!

GET WITH THE CLICK

As you can see from

above, Nama-Damara has some letter s

that English doesn't have. They are /, //, ! and one we don't have a key for

(a vertical line with two shorter horizontal lines through it). (We'll use

a + for it below.) These letters stand for different click sounds that Nama-Damara

speakers use in their language. Why not give them a try? Even if you don't

pronounce them perfectly, at least you'll have fun trying.

s

that English doesn't have. They are /, //, ! and one we don't have a key for

(a vertical line with two shorter horizontal lines through it). (We'll use

a + for it below.) These letters stand for different click sounds that Nama-Damara

speakers use in their language. Why not give them a try? Even if you don't

pronounce them perfectly, at least you'll have fun trying.

The / stands for a sound made by pulling the tip of your tongue softly off the back of your top front teeth while your mouth opens slightly. (It sounds most like the sound, 'nt,' made in English when someone is slightly annoyed, though it doesn't signify annoyance in Nama-Damara.) If you move the tip of your tongue up just a bit, touching slightly above the back of your top front teeth, you'll be in position to make the + sound. It's made by making a snapping sound as you pull your tongue back quickly, with your lips slightly open. For the // sound, you can start with the tip of your tongue in the same starting position as for the + sound, then flatten the top of your tongue against the roof of your mouth, with your lips slightly open. To make the sound, a sort of cluck, you pull the top of your tongue straight down. (The tip of your tongue ends up just sticking out between your teeth a little – or it can even remain where it started). To make the ! sound, you start with your tongue as if you are going to make the // sound, but more firmly pressing against the roof of your mouth. Then, you pull your tongue down and back (not just down) quickly, making a popping noise. Usually, you make the sound of the letter that follows the click symbol at the same time as you make the click. So now what would you say if I said Matisa? to you?

You'll get a chance to practice some more clicking later in this report.

THE KALAHARI: DEBATABLE DESERT

A few weeks ago, Lilia

and I were in the Namib Desert in western Namibia. This week, we were in the

Kalahari Desert in eastern Namibia. Can you find the Kalahari on the ma p?

It's an unusual desert: in fact, some scientists say it is not really a desert

at all, even though all of the maps call it one. It is clear that the Kalahari

was at least once a desert. If you can picture a giant saucer filled with

sand, you'll have an idea of what it is like. It was formed over thousands

of years by wind-blown sand that eroded from soft rocks and settled in the

saucer. Over that period, the sands shifted, traveling slowly on giant dune

waves, just as we reported the Namib sands are moving today. But then, between

ten and twenty thousand years ago, super drought resistant grasses, sedges,

thorn shrubs and acacia trees started growing on the dunes, stopping them

from wandering. So, now, the Kalahari still has sand – and is famous

for its different colored sands – but it is also full of plants. And

it’s the presence of these plants that gives rise to the debate over

the Kalahari’s status today. Some scientists say it should just be called

an arid plateau, or semi-arid bushland, or dry savanna. Here, they call it

bushveld or thornveld. But, whatever you call it, like official deserts, it

gets very little rain, in some parts as little as five inches in a year (in

other parts, up to twenty).

p?

It's an unusual desert: in fact, some scientists say it is not really a desert

at all, even though all of the maps call it one. It is clear that the Kalahari

was at least once a desert. If you can picture a giant saucer filled with

sand, you'll have an idea of what it is like. It was formed over thousands

of years by wind-blown sand that eroded from soft rocks and settled in the

saucer. Over that period, the sands shifted, traveling slowly on giant dune

waves, just as we reported the Namib sands are moving today. But then, between

ten and twenty thousand years ago, super drought resistant grasses, sedges,

thorn shrubs and acacia trees started growing on the dunes, stopping them

from wandering. So, now, the Kalahari still has sand – and is famous

for its different colored sands – but it is also full of plants. And

it’s the presence of these plants that gives rise to the debate over

the Kalahari’s status today. Some scientists say it should just be called

an arid plateau, or semi-arid bushland, or dry savanna. Here, they call it

bushveld or thornveld. But, whatever you call it, like official deserts, it

gets very little rain, in some parts as little as five inches in a year (in

other parts, up to twenty).

THE KALAHARI: UNDESERTED DESERT

So,

the most undesertlike thing about the Kalahari is that it is not deserted.

Along with all of those plants, most of which can survive without water for

ten or more months each year, there are a whole slew of animals that eat those

plants: herbivores, like warthogs and wildebeest; steenbok and springbok;

kudu, eland and oryx; hares and porcupines, springhares and ground squirrels.

And where there are herbivores, of course, there are carnivores: like leopards

and cheetahs; caracals and African wild cats; genets and honey badgers; mongooses

and hyenas. And since there is wood (from the shrubs and trees), of course

there are termites -- and lots of other insects -- so of course there are

insectivores: like aardvarks and aardwolves; bats, suricates and shrews; polecats

and pangolins. Some animals, of course, aren't so picky -- the omnivores –

and the Kalahari has those, too: jackals and bat-eared foxes. There are a

wide variety of birds that eat all of the items on the menu above and are

often on the menu themselves. There are several kinds of tortoises and lizards,

too. Oh, and did I mention .... snakes?

So,

the most undesertlike thing about the Kalahari is that it is not deserted.

Along with all of those plants, most of which can survive without water for

ten or more months each year, there are a whole slew of animals that eat those

plants: herbivores, like warthogs and wildebeest; steenbok and springbok;

kudu, eland and oryx; hares and porcupines, springhares and ground squirrels.

And where there are herbivores, of course, there are carnivores: like leopards

and cheetahs; caracals and African wild cats; genets and honey badgers; mongooses

and hyenas. And since there is wood (from the shrubs and trees), of course

there are termites -- and lots of other insects -- so of course there are

insectivores: like aardvarks and aardwolves; bats, suricates and shrews; polecats

and pangolins. Some animals, of course, aren't so picky -- the omnivores –

and the Kalahari has those, too: jackals and bat-eared foxes. There are a

wide variety of birds that eat all of the items on the menu above and are

often on the menu themselves. There are several kinds of tortoises and lizards,

too. Oh, and did I mention .... snakes?

Because there are

so many plants and animals in the Kalahari, people can also live there. The

San people,  who

have traditionally lived as nomadic hunters, and the Khoi-Khoi people, who

are hunters and farmers, have lived there for hundreds and hundreds of years.

More recently, Herero and Tswana herders have settled in the region with their

goats, sheep and cows; and commercial cattle ranchers graze their animals

on wide stretches of the so-called desert.

who

have traditionally lived as nomadic hunters, and the Khoi-Khoi people, who

are hunters and farmers, have lived there for hundreds and hundreds of years.

More recently, Herero and Tswana herders have settled in the region with their

goats, sheep and cows; and commercial cattle ranchers graze their animals

on wide stretches of the so-called desert.

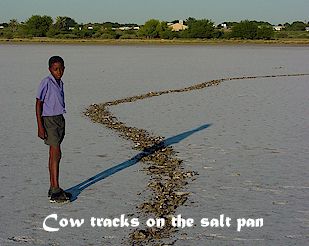

THE KALAHARI: RIVERS AND LAKES IN THE DESERT

Another thing the Kalahari has that you might not expect to see in a desert are rivers and lakes. It has lots and lots of them. The only thing is, they are dry about 95 percent of the time. Once in a great while, it rains heavily enough that water fills the normally dry riverbeds and runs into the normally dry salt pans, forming temporary lakes. When the pans fill up, they are animal magnets, now, in many cases, for farm animals, but also for wild animals. Even when the pans dry up, the animals go there to lick the salt that settles on the ground and gives the wide shallow, depressions a distinctive dancing white sheen under the powerful African sun. Since the Kalahari sands don't shift, the river beds and salt pans remain, for the most part, in the same places they've been for centuries, giving the land a scarred and pocked appearance from a bird's eye view.

Another unusual thing about the Kalahari is that it can get very cold for long periods of time. Other deserts typically get cold at night; but, in the winter (June, July and August), the Kalahari is downright chilly day and night, often with raw, heavy winds. People who live there report that the temperature can get as low as 0 degrees Celsius or 32 Fahrenheit. Brrrrrr! If it weren’t so dry, the Kalahari might even have snow!

MULTI-LINGUAL DESERT SCHOOL

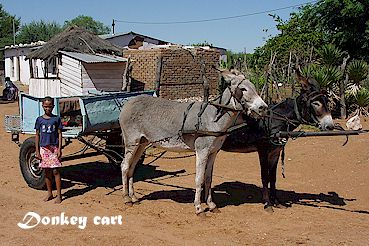

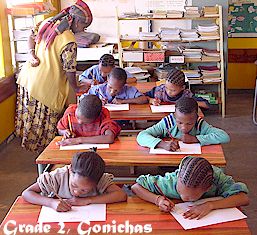

Now,

it’s summer in the Kalahari, so Lilia and I didn’t experience

the desert cold. Last Monday, we visited Gonichas Primary School and Johannes

Doren Secondary School in a town called Gobabis. For the rest of the week,

we visited a school called Mokaleng in a village called Aminuis. Aminuis is

actually divided into three sections, each on a different side of a huge oval

salt pan. The houses in Aminuis are mostly made of wood, mud, cow dung, cement

and tin and the main transportation is donkey cart, a wagon pulled by two

or four donkeys. Each section of Aminuis has one small shop and the village

is surrounded by land that seems uninhabited but actually contains a lot of

small farms, where people raise sheep, goats, cows and donkeys.

Now,

it’s summer in the Kalahari, so Lilia and I didn’t experience

the desert cold. Last Monday, we visited Gonichas Primary School and Johannes

Doren Secondary School in a town called Gobabis. For the rest of the week,

we visited a school called Mokaleng in a village called Aminuis. Aminuis is

actually divided into three sections, each on a different side of a huge oval

salt pan. The houses in Aminuis are mostly made of wood, mud, cow dung, cement

and tin and the main transportation is donkey cart, a wagon pulled by two

or four donkeys. Each section of Aminuis has one small shop and the village

is surrounded by land that seems uninhabited but actually contains a lot of

small farms, where people raise sheep, goats, cows and donkeys.

As we drove into the village, the salt pan looked like a large shimmering lake. I remember when I first saw the pan two years when I visited Aminuis, I said to the friend I was traveling with, 'Wow! It's filled with water!' and he replied, 'No, it's bone dry.' It was a Kalahari illusion.

The pan was empty this time too, but, to our surprise, it did rain once while we were in Aminuis, enough to create a rash of small temporary rivers – but not enough to add any water to the absorbent pan. The desert air is so dry that it evaporates much of the water that falls in lighter rains before it can penetrate the sand or fill the rivers beds.

The night we arrived, we visited the principal's house (right there at the school). We sat outside visiting in the refreshing breeze under a giant sky filled with stars. Since the land is so flat and spread out there, and there are only a few scattered trees, the night sky seems so wide, full and deep. In the desert, the sky is one of the most impressive features and, in the summer, the evening is by far the most pleasant time of day.

Mokaleng is a Catholic mission boarding school with 540 students in grades one through ten. If you saw how small Aminuis is, you would be very surprised that there are so many students at Mokaleng. But, you would be even more surprised to learn that Mokaleng is just one of five schools in the area. Only a few of the students actually come from the village. Most come from the small farms scattered throughout the region, as far as 80 miles away. The students are mostly Tswana (speaking the Setswana language), but there are also San, Herero, Nama-Damara and Kalahari (Khoi-khoi) students. Classes are in Setswana until fourth grade, after which they are in English. Amazingly, even the Herero, Nama, San and Khoi children learn Setswana and English quite quickly. Many of the students are at least tri- or quadralingual, since they also speak Afrikaans, formerly the official language of Namibia. (At the Gobabis schools, the language of instruction till 4th grade is Nama-Damara, after which it is also English.)

DESERT SCHOOL WEB SITE

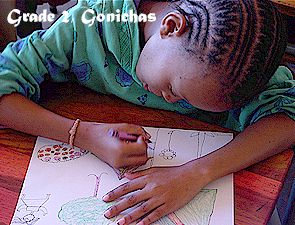

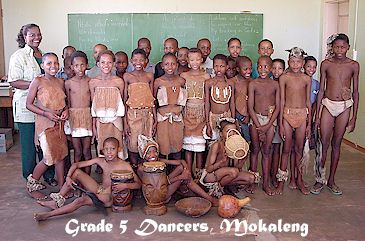

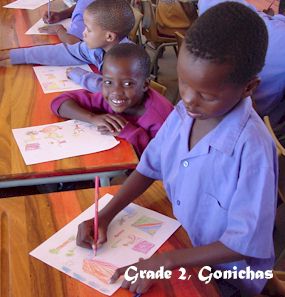

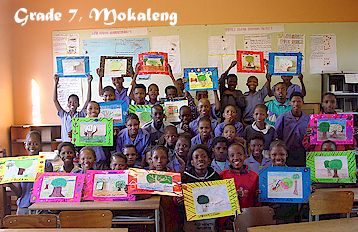

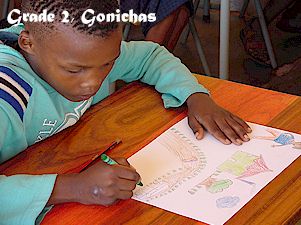

During the week, Lilia

and I visited all 16 of the school’s classrooms (some quick math will

tell you the classes  average

34 students), where the learners (as students are called in Namibia) created

original artwork and picture books for exchanges with U.S. and Chinese schools.

Students made books about African traditions, things they like to do, their

school, desert animals and plants and how to count to twelve in Setswana.

We also made a video of fifth graders performing traditional dances for a

music exchange with a fifth grade class in the U.S. Last year when we visited

Mokaleng, we made a Web site for the school. You can have a look at www.oneworldclassrooms.org/travel/africa/mokaleng/index.html.

average

34 students), where the learners (as students are called in Namibia) created

original artwork and picture books for exchanges with U.S. and Chinese schools.

Students made books about African traditions, things they like to do, their

school, desert animals and plants and how to count to twelve in Setswana.

We also made a video of fifth graders performing traditional dances for a

music exchange with a fifth grade class in the U.S. Last year when we visited

Mokaleng, we made a Web site for the school. You can have a look at www.oneworldclassrooms.org/travel/africa/mokaleng/index.html.

While visiting Mokaleng, we ate our meals each day with the Catholic sisters who run the school and the school’s American WorldTeach volunteer. The sisters told us a bit about the school history. It was founded in 1902 when community members drove an oxcart (with twelve oxen) six weeks to Windhoek (now the trip takes only four of five hours by car) to request that a priest be posted to their village. When the priest arrived, the people made him a traditional house and he started holding classes right there in the house. The school has grown a lot over the years. You can read more about the school’s history on the project Web site.

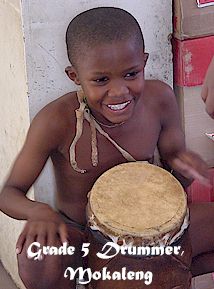

DESERT SONG AND DANCE

At

Mokaleng, Lilia and I were most impressed by the incredible singing and dancing

talent exhibited by the students. The school’s Cultural Group, dressed

in traditional clothing made of animal skins, ostrich beads and camel thorn

pods, performed for us one evening. We were really amazed and thoroughly entertained;

but we actually experienced many mini-performances all week long. The students

sang and danced for Lilia in many of the classrooms she visited and even as

we walked around the school grounds, students would spontaneously start singing

and dancing for us in full harmony and in perfect synchronization. Even the

first graders are very talented – as if they were born singing and dancing!

At

Mokaleng, Lilia and I were most impressed by the incredible singing and dancing

talent exhibited by the students. The school’s Cultural Group, dressed

in traditional clothing made of animal skins, ostrich beads and camel thorn

pods, performed for us one evening. We were really amazed and thoroughly entertained;

but we actually experienced many mini-performances all week long. The students

sang and danced for Lilia in many of the classrooms she visited and even as

we walked around the school grounds, students would spontaneously start singing

and dancing for us in full harmony and in perfect synchronization. Even the

first graders are very talented – as if they were born singing and dancing!

CLICKING TO TEN IN NAMA-DAMARA

At Gonichas and Mokaleng, some students taught us how to count to ten in Nama-Damara. Try your tongue on this:

1.

/gui

2. /gam

3. !nona

4. haka

5. koro

6. !nani

7. hu (pronounced nasally)

8. //khaisa

9. khoese

10. disi

(Note: The vowels

are pronounced ah-ay-ee-oh-oo and the stress is on the first syllable.) So,

if you still have the Swahili numbers from the second report, can you tell

if Nama-Damara is a Bantu language, i.e. related to Swahili?

============================

KALAHARI MATH PUZZLER

So, here's a related math problem for you. The Kalahari gets as little as five inches of rain on average per year in its driest regions. The Amazon rain forest, in South America, on the other hand, gets as much as 300 inches of rain on average in its rainiest regions. So, first, express the ratio of Kalahari rain in relation to Amazon rain using a fraction in its simplest form. How many years of rain in the driest parts of the Kalahari would it take to match one year's amount of rain in the wettest parts of the Amazon? How many centuries of rain in the driest parts of the Kalahari would it take to match ten years of rain in the wettest part of the Amazon? How many feet of rain would fall in the wettest part of the Amazon during that same number of centuries? How many miles is that number of feet, rounded up? I'll tell you the answers next time.

GUESS WHO ANIMAL POEM

Here’s a guess-who poem featuring an animal Lilia and I saw in the Kalahari this week. Guess who!

Ngiri

Attention

all readers

Attention all listeners

Join my contest today

I'm searching for a brand new moniker

My old one I'm throwing away

Attention

all readers

Attention all listeners

If you want to win fortune and fame

Please give me a brand new label

A more dignified, complimentary name

One

that doesn't refer to the blemishes that protrude from my face

Or at least one that puts them in a good light so I don't feel a disgrace

One that doesn't refer to my relatives as if we're an ignoble lot

One that instead emphasizes the overlooked positive qualities I've got

Like

my gentle manner, my shy unobtrusive way

Like my humble habit before eating of kneeling down to pray

Maybe one that refers to my shapely derriere

Or the spring I've got in my tail, or my slick gray beard and hair

If

you tag me with a new designation, I'll be forever grateful to you

Please, anything other than my current title would more than nicely do

And I'm sure you'd like to know if you win what you'll get for a prize

Maybe I'll dig you up a root with my tusks - or some other similar surprise

Attention

all readers

Attention all listeners

Send your entry in today

For there'll be no surprise for any who delay!

============================

By the way, the answer to the last report's poem is the zebra. We’ll give you the answer to this report’s poem next time. Or, you can visit Safari! on the project Web site at www.oneworldclassrooms.org/travel/africa/safari/index.html to encounter many African animals through poetry and photography.

QUESTIONS AND ANSWERS

Here are some more answers to your questions, this time answered by second, fourth and eighth graders at Mokaleng.

This set of questions was answered by fourth graders:

1. What are your traditions about marriage? People here get married at about 25 years old. The man would go to the woman's house to ask for her parents' permission to marry their daughter with at least 5 cows as dowry. Of course, the richer the man is, the more cows he would bring.

2.

What tribe are you from? In our class the majority of the students are

Setswanas. There is one student from the tribe called Herero. A few students

are Sans, Namas and Kalaharis.

2.

What tribe are you from? In our class the majority of the students are

Setswanas. There is one student from the tribe called Herero. A few students

are Sans, Namas and Kalaharis.

3. Who is your favorite artist and what is your favorite type of music? Some of us like Michael Jackson and Mariah Carey. We like African musicians like Mike Bohitile and Jackson Kaujeua. We also like a very famous South African singer called Brenda Fassie. We call her the Madonna of South Africa. Our favorite types of music include Gospel, soft music and disco. We also like the traditional tribe music very much, such as Borankana and Pitsharas.

4. What type of dancing do you do? We love to sing and we love to dance. The ones that we can name are called Borankana and Mbaqanga.

5. What type of food do you eat? We eat porridge, rice, donkey meat, goat, lamb, horse, macaroni, pap (a corn meal dish), eggs, bread, tea, cheese, and sometimes the sisters bring canned fish from another town so that we can all taste fish. We also pick berries and fruits from the desert, and we like to eat gumballs made of dry sap from thorn bushes.

6. What subjects do you study? We study English, Setswana, Handwriting, Social Studies, Mathematics, Natural Science, Crafts, Information Science, and Physical Education.

7. What do you want to be when you grow up? We want to be doctors, nurses, teachers, singers, priests, nuns, policemen, farmers, ministers, soccer players, and the president of Namibia.

This set was answered by eighth graders:

1.

What is it like living in Africa? We like it here.

1.

What is it like living in Africa? We like it here.

2. What's the average temperature where you live? In the summer the temperature can get as high as 100 degrees and in the winter it can get as low as 32 degrees.

3. What time does your school day begin and end? It begins at 6:30 in the morning and ends at 12:30, but we also have study periods in the afternoon and evening.

4. What kinds of things do you like to do? We like to play netball, soccer, run, swim in the salt pan when it has water in it, watch TV, read in the library and make cars out of wire. We especially like to sing, dance and play singing games. We all want to perform in the Culture Group.

5. How do you travel in Namibia? We don't travel very much since we all live in the school. But mostly people travel in cars and sometimes buses. We go by donkey carts when traveling around the nearby areas or we walk.

This set was answered by second graders.

1. What clothes do you wear? We wear shirts, skirts, pants, shorts, dresses and school uniforms. We wear traditional clothes when we perform traditional singing and dancing.

2.

Where do you play after school? Our school is a boarding school, so we

stay on the campus after school. We play soccer, netball, basketball and jump

rope. We also like to play in the playground, where we can play on the swings

and slides.

2.

Where do you play after school? Our school is a boarding school, so we

stay on the campus after school. We play soccer, netball, basketball and jump

rope. We also like to play in the playground, where we can play on the swings

and slides.

3. What language do you speak? Most students at our school speak Setswana, so Setswana is used as the teaching language from 1st to 4th grade. English is the teaching language for 5th to 10th grade students. There are also many students from other culture groups, so they speak their own languages as well – Herero, San, Nama and Kalahari. We also speak Africaans, the former official language of Namibia, which is still widely spoken.

4. What are your names? The girls have names like Jeanett, Jolanda, Uandjoza and Chrisanctus. The boys have names like Fritz, Markus, Philipus and Mbakondja.

5. What is the landscape like in Namibia around your school? We are in the Kalahari Desert so the ground is sand. Where we are, it’s very flat with lots of small thorn bushes and one very large salt pan.

6. How many kids are in your school? There are 540 students at our school, from grade 1 to grade 10.

7. How do you get to school? Some of us walk to school. Some of us take the donkey carts or cars. We stay at the school for months at a time and return during vacation.

8. What makes you special? One student said being clean made her feel special. Some thought that their eyes, noses, faces and hair made them feel special. Some of the students thought that being good at a subject like Math, Writing and English made them feel special. Some others thought that when they sing, dance or draw, they feel very special.

9.

What do you use to make music? We sing and dance a lot. We use our feet

to make rhythm or play  drums

for the beat. We can also make percussion instrument by putting a string through

a lot of beer bottle tops or Coke cans.

drums

for the beat. We can also make percussion instrument by putting a string through

a lot of beer bottle tops or Coke cans.

10. What food do you eat? Do you go to restaurants? We eat porridge, meat, fish, vegetables and fruits. If we go to a bigger town where there are restaurants, sometimes we can eat there with our families.

11. What kind of homes do you live in? Our houses are made of bricks, dry grass, cow dung, wood and tin.

12. What’s the weather like? It’s very sunny and windy right now because it’s summer time here. It’s a little chilly in the morning but gets quite hot during the day. When the winter comes, the temperature drops and it can get as cold as 0 degree centigrade.

========================================================

THAT’S ALL FOR NOW

Well, that's it for this report. Till next time, learn lots!

Paul Hurteau and Lilia

Cai

Africa School Project Coordinators

<><><><><><><><><><><><><><><><><><><><><><><>><><><><><><><>

Teachers: Hopefully, the clicking activity at the top of this report will serve as a fun language arts activity, seeing how well students can listen (or read) and apply the instructions to produce something close to correct sounds. It also highlights the range within human languages and cultures.

Visit the Mokaleng School Web site at www.oneworldclassrooms.org/travel/africa/mokaleng/index.html.

Here are some Web sites about the Kalahari:

www.stuart.iit.edu/botswana/kalahari.html

www.southafrica-travel.net/kalahari/e6kala05.htm

www.ecologychannel.com/gallery/kalindx.htm

[Photo Gallery]

www.worldandi.com/public/2000/january/safari.html

www.infoplease.com/ce6/world/A0826902.html

<><><><><><><><><<><><><><><><><><><><><><><><><><><><><><><><><><><><><><><><>