E-Travel Log #8: Xishuangbanna - The Rain Forest of China

Attention Teachers: Please see teacher notes below.

Dear Students:

Ni men hao ma? (How

are you?) In this travel log, we’re going to hitch a ride on a fishing

boat and float do wn

off the Tibetan Plateau into the Xishuangbanna Rain Forest region

of China. Once we get there, we’ll visit a rain forest market, meet

some students and consider a worldwide debate. We’ll also tell you a

story called Cao Chong Weighs an Elephant; challenge you with more

guess-who Asian animal poems; and list more answers to your questions. Enjoy!

wn

off the Tibetan Plateau into the Xishuangbanna Rain Forest region

of China. Once we get there, we’ll visit a rain forest market, meet

some students and consider a worldwide debate. We’ll also tell you a

story called Cao Chong Weighs an Elephant; challenge you with more

guess-who Asian animal poems; and list more answers to your questions. Enjoy!

THE TIBETAN PLATEAU: SOURCE OF CHINA’S GREAT RIVERS

If you look at an elevation map of China, like the one at http://www.askasia.org/image/maps/ele_china.htm, you’ll notice that the land on the western side of the country is much higher than the land on the eastern side. That’s because the land on the western side is a giant plateau: the Tibetan Plateau* – also known as the Roof of the World. Rising above this country-wide roof, are the world’s tallest mountain ranges, among them the Himalayas, which include the world’s tallest mountain, Mount Everest. From the mountains and the plateau, high above sea level, the land slowly slopes downward till it reaches the Pacific Ocean.

So, if you can picture this in your head – a massive rooftop, crowned with mountain ranges, connected by several slowly descending steps to a giant pool of water, you’ll have a general idea what China looks like, topographically speaking. Also, you’ll understand why China’s major rivers, including the Yangtze, Yellow and Mekong Rivers, all begin on the Tibetan Plateau and, yielding to gravity, flow all the way down Asia’s sloping land and empty into the Pacific Ocean.

(*Note: The Tibetan Plateau is also called the Tibetan-Qinghai Plateau.)

MILES ABOVE THE REST

Mount Everest is 29,035 feet above sea level. One mile is 5,280 feet; so, how many miles high is Mt. Everest?

The Yangtze River, at 3,900 miles long, by the way, is China’s longest and the world’s third longest. Do you know which rivers in the world are longer? The Yellow River, which we already crossed at Xi’an and Lanzhou, is China’s second longest at 3,395 miles. The Mekong (2,610 miles) flows through China, Myanmar, Laos, Thailand, Cambodia and Vietnam.

FLOATING DOWN THE MEKONG

So,

we’re up on the Roof of the World and there are all these rivers

flowing down off the plateau to the ocean. So, what do you say we float down

one of them? We’ve seen cities, deserts, plateaus, mountains and grasslands

so far on our trip through China, so let’s take the Mekong since

that will lead us to a different habitat.

So,

we’re up on the Roof of the World and there are all these rivers

flowing down off the plateau to the ocean. So, what do you say we float down

one of them? We’ve seen cities, deserts, plateaus, mountains and grasslands

so far on our trip through China, so let’s take the Mekong since

that will lead us to a different habitat.

XISHUANGBANNA: A RAIN FOREST OF RUBBER TREES AND RICE

Far beneath the plateau,

the current slows and we suddenly notice a few dramatic changes. First, it’s

uncomfortably hot and humid: we are starting to feel a bit like soggy toast.

Next, small swarms of insects are dive-bombing us, as if it’s their

job to annoy us in our sticky discomfort. But, if we can get our minds off

the unpleasantries and take a look around, we also see that the mountains

here are much lower and covered with trees – and everywhere we look

it’s green! We’ve reached Xishuangbanna, China’s

tropical rain forest! Like other tropical rain forests, this one, which stretches deep into the Asian

countries south of China, features an incredible diversity of plants and animals.

But as we coast down the Mekong in this lush environment, something seems

a little strange…

other tropical rain forests, this one, which stretches deep into the Asian

countries south of China, features an incredible diversity of plants and animals.

But as we coast down the Mekong in this lush environment, something seems

a little strange…

We park our boat and walk up one of the mountains. Yes, it’s covered with trees; but, oddly, they are all the same. They have whitish bark with unnatural black slashes on their trunks. Beneath the slashes, each trunk has a little black spout with a bucket under it. A thick whitish liquid drips from the spouts into the buckets. No, they are not maple trees: they are rubber trees – and their milky sap is called latex, the natural resource from which rubber is made.

At the top of the mountain, from a small clearing, we can see out across a long and wide valley between many other mountains. The valley is also very green, but completely void of trees, for it is filled with rice fields.

WORLDWIDE DEBATE: RICE VS. FOREST

While

some patches of pure rain forest still exist in Xishuangbanna, most of it

has been uprooted and replaced by rubber trees and rice plantations. Not surprisingly,

many plants in the area have become extinct and many more are endangered

due to deforestation. The same goes for many animals that made their

homes and got their food from those plants. While a small number of tigers,

elephants, leopards and golden-haired monkeys remain, they are few and far

between. In fact, the Xishuangbanna Rain Forest itself is severely endangered.

While

some patches of pure rain forest still exist in Xishuangbanna, most of it

has been uprooted and replaced by rubber trees and rice plantations. Not surprisingly,

many plants in the area have become extinct and many more are endangered

due to deforestation. The same goes for many animals that made their

homes and got their food from those plants. While a small number of tigers,

elephants, leopards and golden-haired monkeys remain, they are few and far

between. In fact, the Xishuangbanna Rain Forest itself is severely endangered.

Shouldn’t something be done to save what’s left of the Xishuangbanna and its plants and animals? Many argue it should. But others point out that China needs rice to feed its 1300 million people and cash crops to improve its standard of living – and the Xishuangbanna has lots of land, rain and sunshine, a perfect garden environment. Even the United Nations has declared 2004 the International Year of Rice, choosing the theme ‘Rice is life.’ The UN argues that rice provides over 60% of the energy intake for over 2 billion people in Asia alone – and it provides work and income for millions as well.

Where do you stand on the issue? Maybe your class can stage a debate to explore the pros and cons on both sides. ‘People Versus Plants and Animals’ is a debate that applies to all of the world’s tropical rain forests, all of which are shrinking because people are using the land to make a living.

BUTRESSES AND DRIP TIPS

By the way, do you

know how to tell a tropical rain forest tree from just a regular old tree?

Well, there are a very wide variety of tropical trees out there, so they don’t all fit the

same mold; but in general they have one or more of the following features:

wide variety of tropical trees out there, so they don’t all fit the

same mold; but in general they have one or more of the following features:

* Buttresses

*Large leaves (on saplings of emergent layer species and on understory

species)

* Leaves with drip tips (on saplings of emergent layer species and

on understory species)

*Thin bark

* Smooth bark

* Bark with spines or thorns

* Cauliflory (the development of flowers (and therefore fruits directly

from the trunk, rather than at the tips of branches)

* Large fleshy fruits

There’s a good reason for each of these characteristics, if you consider

them scientifically. Any hypotheses?

BAMBOO: A RAIN FOREST WORK HORSE

Bamboo is a highly versatile plant that is both indigenous to and planted in Asian rain forests. Besides being the favorite food of giant pandas, here’s a partial list of how people put it to use:

* Food (bamboo

shoots)

* Construction (houses, bridges, scaffolding, etc.)

* Transportation (rafts, boating poles)

* Fishing and hunting (fishing poles, fishing nets, spears, bows and

arrows)

* Ladders

* Tool handles

* Furniture

* Musical instruments

* Sleeping mats

* Flowerpots

* Lampshades

* Chopsticks

* Fans

* Umbrella handles

* Baskets

* Purses

* Walking sticks

* Pipes

* Hats

* Sandles

Can you add anything to the list? In Chinese culture, bamboo symbolizes gentleness, modesty and serenity.

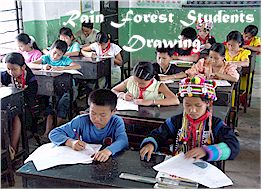

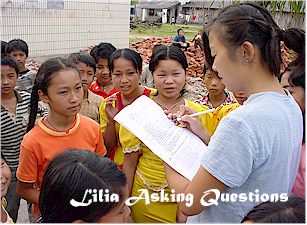

RAIN FOREST SCHOOLS AND MARKETS

While in Xishuangbanna,

we visited a market and a school. We’ve included photos of both in this

report. At both, we encountered more Chinese ‘minority’ ethnic

groups, the Dai, Aini (or Hani) and Akha. The photos show their colorful traditional clothing.

photos show their colorful traditional clothing.

ONE COUNTRY: DIFFERENT CULTURES

In our last travel

log (when we visited students in Xiahe on the Tibetan Plateau), we talked

about things that go to make up a life – and a culture. How do you think

the culture of Tibetan children from the plateau differs  from

that of Aini or Dai people from the rain forest? In what ways do you think

their lives are similar and in what ways different?

from

that of Aini or Dai people from the rain forest? In what ways do you think

their lives are similar and in what ways different?

CAO CHONG WEIGHS AN ELEPHANT

Here’s a story featuring the rain forest’s largest animal – and a boy named Cao Chong who was clever enough to figure out how to weigh one. Cao Chong was the son of Cao Cao – a famous emperor during the time of the Three Kingdoms around 200 A.D.

One day, guests from afar brought an elephant to Cao Cao as a gift. Since elephants are from southern Asia, Cao Cao’s people had never seen one before. While they were commenting on the size of this giant animal, Cao Cao asked his wise men how much this elephant weighed. The wise men, with their long white beards, looked at each other and didn’t know what to answer. They were all thinking, the elephant was huge and there was no scale in the world that would be big enough to weigh it. Cao Cao became a little upset. He bellowed, ‘How come with all the wisdom in my country, I can’t even figure out how much an elephant weighs?’

At this moment, a child stepped out and said that he had a way to figure it out. It was Cao Cao’s six-year-old son, Cao Chong. Everybody laughed, but Cao Chong didn’t care. He ordered everyone and the elephant to go to the river. There was a big boat in the river so he had the people lead the elephant onto the boat. While the boat sank lower, he told the boatman to mark the water level on the side of the boat. Then he had the people lead the elephant off the boat and told them to fill the boat with rocks. When there were enough rocks on the boat, the boat sank again into the water to where it was marked. Then Cao Chong told the people to weigh the rocks one by one and add up the weights. The total weight was – what the elephant weighed!

TOO SMART, TOO BAD

Do you think Cao Chong was clever? Well, unfortunately, because he was so intelligent, his older brother was very jealous and afraid that Cao Cao was going to make him the heir. After Cao Cao passed away, the brother put Cao Chong into jail, where he spent the rest of his unhappy life. In jail, Cao Chong wrote a famous poem in which he implied the question to his brother, ‘We were born from the same root, why are you so anxious to hurt me?’ It’s a line that many Chinese parents still use today – when brothers or sisters or cousins are not behaving nicely to each other.

GUSHI POETRY

Here’s the gushi that Cao Chong wrote:

Zhu

dou ran dou ji,

Dou zai fu zhong qi.

Beng shi tong gen sheng,

Xiang jian he tai ji!

Notice the rhyme scheme and the number of syllables in each line. The translation is:

Beans

boil over beanstalk fire

The beans cry in the pot:

We are born from the same root

Why are you so anxious to burn me?

In the poem, the fire is made of dried beanstalks; so the beans are asking the question to the beanstalks.

WRITING GUSHI

In the last report,

we mentioned that, when writing gushi, we can’t get across as much meaning

using English as a writer using Chinese could in five or seven syllables. Did you figure out

why? It’s because in Chinese all words are only one syllable long and

in English many words have more than one syllable. So, if we choose multi-syllable

words for our lines, we have to use fewer words to get the syllable numbers

correct and maintain the traditional rhythm. In the pangolin poem from the

last report, for example, we only used two words, Chinese medicine, to reach

five syllables, whereas in Chinese those two words – zhong yao – are only two syllables long.

a writer using Chinese could in five or seven syllables. Did you figure out

why? It’s because in Chinese all words are only one syllable long and

in English many words have more than one syllable. So, if we choose multi-syllable

words for our lines, we have to use fewer words to get the syllable numbers

correct and maintain the traditional rhythm. In the pangolin poem from the

last report, for example, we only used two words, Chinese medicine, to reach

five syllables, whereas in Chinese those two words – zhong yao – are only two syllables long.

Real gushi often uses conventional word-combination patterns, such as adjective-noun-verb-preposition-adjective-noun. In English, we can’t always follow such a pattern and still make the line only five or seven syllables. Still, it’s lots of fun to write English gushi. Maybe you can choose an animal and give it a try! (We’ll tell you more about gushi next time.)

GUESS WHO

Here are five more guess-who animal poems written in gushi form. This time, they are all rain forest animals. Guess who!

Animal #1

Shaggy man of the forest

Lanky arms longer than legs

Beast's face, philosopher's eyes

Why do wonders fade and die?

Animal #2

No need for poison

Sssimple sssqueeze will do

Says, 'Call me Uncle!'

Then it swallows you!

Animal #3

Grim

hollows, deceptive shades

Hood held high, threatening death

Lightening strikes and all turns black

Who knows which is our last breath?

Animal #4

A

troupe of golden sun rays

Splashing through the canopy

Munching leaves and sipping dew

Shouldn't we spare the precious few?

Animal #5

King displays a flashy gown

Queen's grandest, but wears just brown

Renowned for pomp and for grace

Throne's threatened by biped race

The answers to the

poems in the last report are the yak and the pangolin. You can

read lots more guess-who  Asian

animal poems written in gushi form – and see photos of the animals --

by visiting the project Web site. Your teacher has the address.

Asian

animal poems written in gushi form – and see photos of the animals --

by visiting the project Web site. Your teacher has the address.

Q & A EXCHANGE

Here are more answers to your questions. These questions were answered by (mostly) fifth grade students at the Jinha Elementary School in Jinha in the Xishuangbanna Rain Forest region of Yunnan Province.

1. What is the weather like where you live? How often does it rain? Do you ever get flooded? We live in the rain forest so it’s often hot and humid. In the rainy season, it can rain several times a day; but in the dry season, it goes for weeks without raining. We don’t live that close to the river so we don’t get flooded.

2. What do you do in your spare time? Do you go on vacation? We play games, watch TV, read books and play sports during our spare time. We have summer and winter vacations.

3. What is a day in your school like? We have classes in the morning from 7:30 to 11:30. It gets too hot to have classes around noon, so we eat lunch and nap. The afternoon classes don’t start till 3:00 PM and we finish school at 4:30. Some students live at the school so they have a self-study time every night. We play soccer, basketball and ping-pong during the breaks.

4. What do your houses look like? Our houses are mostly made of bricks and wood, with tiled roofs. They are lifted above the ground by logs or columns made from posts or bricks. They are mostly gray and black.

5. What kind of food

and medicine do you get from the rain forest? We get

all kinds of fruits like coconuts, pineapples, bananas, plums and mangos.

We use banana leafs for cooking. There are also many kinds of  herbal

medicines we get from the rain forest, like bracken fungi, roots, teas made

of leaves and grasses, barks and fruits.

herbal

medicines we get from the rain forest, like bracken fungi, roots, teas made

of leaves and grasses, barks and fruits.

6. What do you consider a special treat? Rice and sesame cooked in banana leaves is a special treat for us, and we eat it during festivals.

7. Do you ever see endangered animals in the rain forest? Yes, we see all three kinds of peacocks – blue, green and white, which are all endangered. We also see pangolins and deer.

8. What holidays do you celebrate? The Dai people’s biggest holiday is the Water-Splashing Festival, which is in April. Over the years, it has become a major tourist attraction, and hundreds of thousands of people gather in Xishuangbanna to participate in the celebration by throwing buckets of water on everyone else. The government also hosts parades featuring people wearing all different colorful costumes of the ethnic groups in Yunnan Province. Hani people’s biggest holiday is New Year’s Day, which is called Gakapa in their language and tradition. They all dress up in their best traditional outfits and have feasts for the celebration.

9. What kind of pets do you have? We have cats, dogs and parrots.

10. How many languages do you speak? We speak Chinese Mandarin, Dai and Hani. Some of us know a little Japanese and Korean.

11. How much homework do you have and how long does it take you? About one or two hours a day.

12. Can the temperature be over 100ºF? Rarely.

13. What kinds of animals do you like? We like puppies, kittens, peacocks, birds and pandas.

14. When you look out your windows at home, what do you see? We see the sky, trees, mountains, rice fields, butterflies, dragonflies, geckos, insects, ants, chickens, pigs, donkeys, geese, monkeys, parrots and snakes.

15. Do the families have televisions and what shows do you like to watch? Most of us have TVs at home, and we like to watch cartoons, comedy shows and TV dramas.

16. What is it like living in a communist country? Are there restrictions? How is it different from living under other governmental systems? We are happy living in our country. We don’t know of any restrictions. We don’t know about other governmental systems.

17. Do you like candy? Yes, we like candy and other sweet things like milk

tea and fruits.

18. What do you daydream about? We daydream about traveling afar to a foreign country, flying and becoming actors and actresses when we grow up.

19. What are your goals? We want to be dancers, scientists, movie stars and drivers.

20. What music do you listen to? Do you play an instrument? We listen to pop music from Hong Kong, Taiwan, Japan, Korea and Mainland China. We also have some traditional music that we like. We play piano, drum, keyboard, flute and gourd flute.

THAT’S ALL FOR NOW

That’s all for this travel log. In our next report, we’ll take a bus from Xishuangbanna to two other famous towns in Yunnan Province, Dali and Lijiang. Till then, learn lots! Zai jian!

Paul and Lilia

China Project Coordinators

====================================================

Teachers:

Here are a few links to excellent Web sites related to this travel log:

http://www.oaklandzoo.org/atoz/asia.html -- Asian rain forest animals.

http://www.bsrsi.msu.edu/rfrc/deforestation.html -- All about deforestation.

http://kauai.net/bambooweb/bambooslides/boomenu.htm -- All about bamboo (where we borrowed the bamboo image from).

http://www.fao.org/rice2004/index_en.htm -- The UN’s International Year of Rice page (where we borrowed the rice image from).

www.lonelyplanet.com/dest/nea/graphics/map-chi.htm -- Physical map of China – and information.

www.nationalgeographic.com/resources/ngo/maps/view/images/chinam.jpg -- Physical map of China.

http://www.thewaterpage.com/images/MekongMap.jpg -- About the Mekong River. http://www.oneworldclassrooms.org/travel/china/tour2/index.html

E-Travel

Log #8: Xishuangbanna - The Rain Forest of China |